The idea of finding ourselves and losing ourselves are the same thing. The creative process is both introspective and extrospective… We sometimes need the willingness to leave the paddock and our own preconceptions of ourselves behind…”

William Grob

The following interview forms part of a series where I invite contemporary artists to each reflect on their personal history, meaning, and philosophy, and how those are embedded throughout their creative process.

This week I talked with figurative painter William Grob, who lives between Berlin and the UK. In his words, William was “an artist before [he] could talk”, due to growing up with a severe speech disorder which profoundly affected his life, and meant he was unable to express himself verbally until the age of seven. As William’s “mother tongue”, art became a means for him to express emotions using colour and form. In our interview, William discusses how he explores challenges of communication through his projects, such as ‘Lost Millennials’, as well as how individualism shapes the art world, and his thoughts on the stereotype of the ‘tortured artist’.

Tell me about your project, ‘Lost Millennials’.

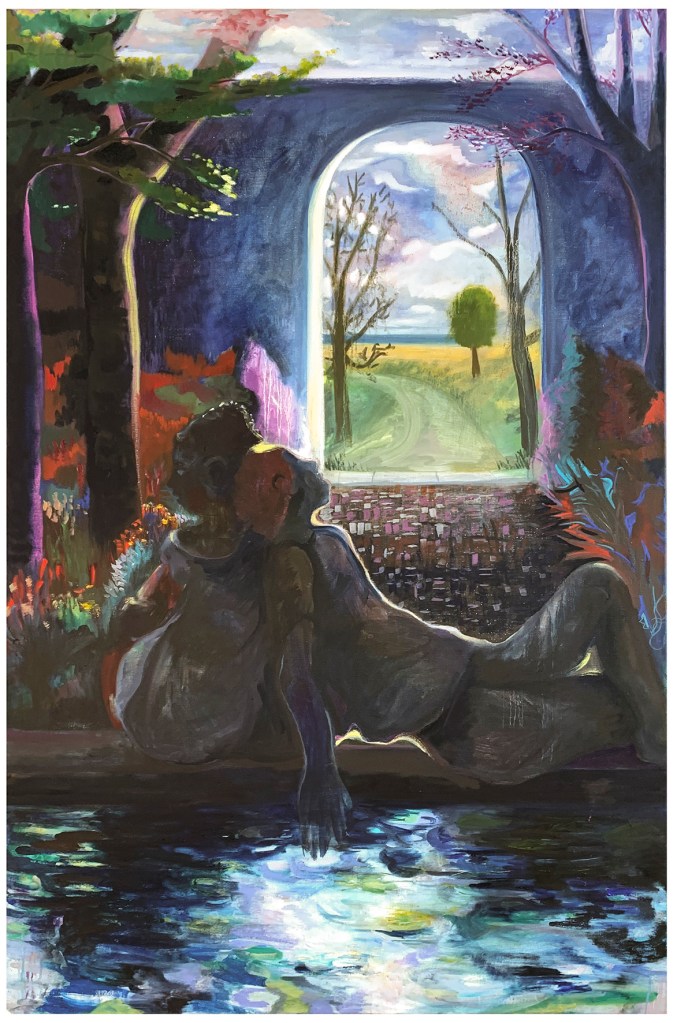

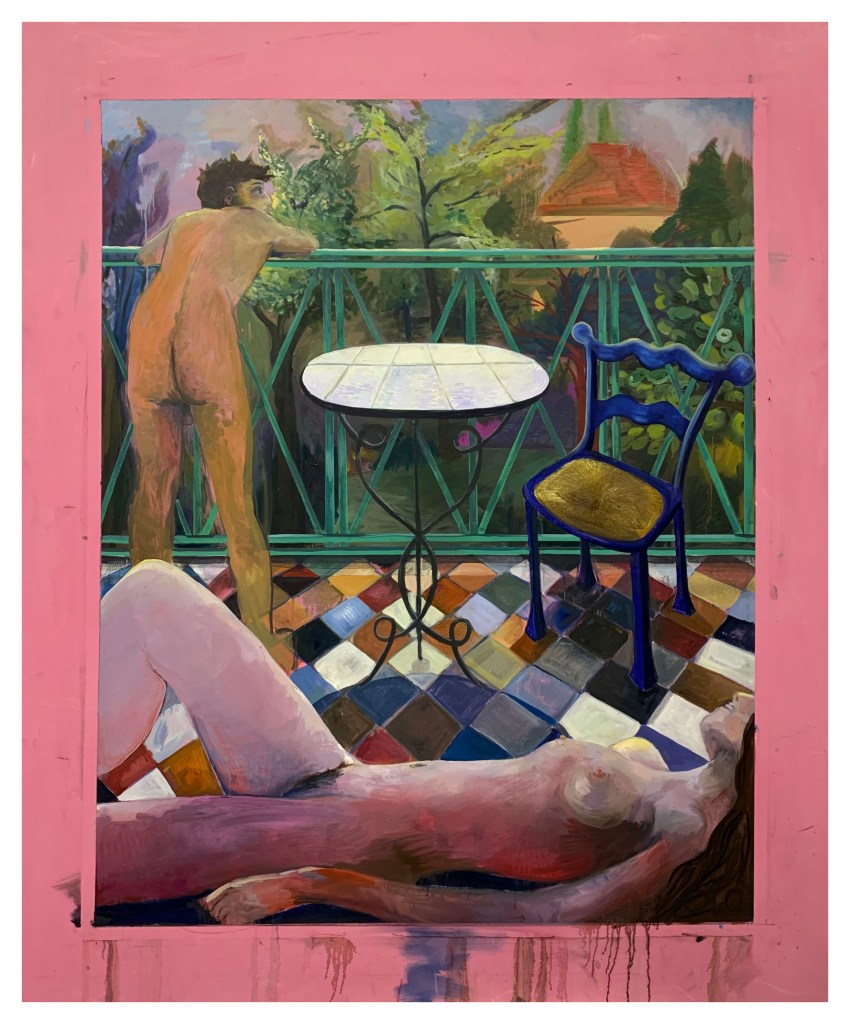

Lost millennials is a bit of an enigma. It started at the end of 2019, as a way to try and decipher how I see the world. Wards of slightly awkward moments, gazing into dreams, watching people watch people and then create a scene from that. Well, at least that’s how it started. As I delved into my series after a few months, and a few key works. (‘Alone we are lost, may the bar stay alight’, 2019) The pandemic hit us and all of a sudden the work became all too real. The series which started off as a playful comment on the ‘Millennial’ “lost, but happy” as a friend called it, I realised what I was exploring was the challenges of communication and the mutability of memory. Which has been exacerbated by the abundance of information and the ease with which it can be manipulated. I think it’s incredibly important to be critical and mindful of how we communicate In our digital age. As Sartre said “language is the source of misunderstandings”, which comes close to heart as I grew up with a speech disorder, unable to communicate as a child.

I find the title can also be misleading, which I love, because I see the work as a positive take on society, that WE can break away from technology and we can find time and space in our busy environment to ‘recharge ourselves’, I think this is why I hold off from adding any form of ‘technology’ to the paintings, my subtle nod towards enjoying a moment without a tech interrupting us. All the imagery for the series comes from imagination, which blends these memories and these fantasies together. In the words of Marcel Proust, ‘the only paradise is a paradise lost’ – I like to think that the paintings create an environment that gives the subject the space to reflect on the emptiness from the abundance of information.

By stripping away this information and placing the viewer in a neo-figurative world, I invite them to leave behind their own burdens and engage in a conversation about the times we live in. The paintings do not seek to exaggerate the current situation or to overwhelm the viewer with bleakness, but rather to offer a glimmer of hope at the end of an empty road. The fundamental question at the heart of the series is, where do millennials go from here?

It’s written that your works focus “on the line between reality and the psychic world… between the real and the imagined…” What have been the greatest challenges capturing those realms and spaces between?

There are always challenges in expression, as expression can be miss interpreted. The works are ambiguous, readable in many forms. I guess the greatest challenge in capturing the spaces between reality and psychic world is finding a way to effectively convey the intangible and ephemeral nature of these realms. They are often complex dreams or intangible experiences with emotional depth that cannot be directly translated into a two-dimensional painting. Like anything in life it’s a pendulum. Finding that true balance between these extreme fantasies and these direct memories. I think it’s important for the paintings to feel grounded, which leans towards the ‘direct memory’ allowing the viewer to see the physical world of the painting, while also incorporating a flicker of abstracted fantasy. Kind of like the visual version of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ by Gabriel García Márquez

Would you say the cultural trend of individualism is overall beneficial or detrimental to the art world?

I think that’s hard to say. On the superficial level, of course individualism is positive and helps us evolve to the time we live in; if we didn’t, we’d be left in a dated society. It allows artists to express their unique perspectives and experiences and relay that on to someone(s) who could have had a similar experience, and it helps to evolve the art scene by bringing new ideas and perspectives into the mix. That leads to a challenging art scene.

With that it also leads to extreme trends. “Everyone’s individual”, therefore we’re still put into categories and labelled by ‘style’. Individualism can also create a competitive and cut-throat environment, where artists can feel pressured to ‘stand out from the crowd’. This can create a homogenised and narrow view of what is considered ‘valuable’ within the art world. Individualism runs the risk of becoming selfish, which can lead to art feeling more like a product, bought and sold, rather than an emotional experience that connects us culturally. But maybe that’s just the art world today and it has nothing to do with the individual, it’s just society in general.

As an artist, how can one talk about certain subjects without being too on the nose or disingenuous?

We have to find the genuine, we have to speak from truth otherwise we fall into the rest of the bullshit that is floating around. I feel I have also always been quite ambiguous with the imagery and stories of my work. The thought should never be boxed in my mind, otherwise we cut off potential threads of ideas.

I am always looking for someone’s different perspective of my own work. I love those moments, when someone comes up to me and explains how they perceive the work, and I usually look at them in amazement, as it’s never how I imagined it to be seen. That’s a genuine connection which opens conversations rather than closes. All because the idea is not fixed.

It’s also how I work, the painting is never fixed before I start, every day something is added and usually something is taken away. It never feels like the drawing from the beginning but the drawing from the beginning is always there as its foundation.

How do you feel about the stereotype of the ‘tortured artist’?

As I say in the studio, “got to put the PAIN in painting.” For me, I feel my best work comes out when my emotions are out too. From throwing paint brushes to shredding tears. All emotional forms I embrace and most of the ‘tortured’ ones stay in the studio. I also think its what keeps momentum pushes us to go further. This self-inflicted pain is essential, otherwise what motivation would we have if when we finished a painting to start a new one? One of my favourite painters is Philip Guston and to paraphrase him, he talks about his intense battles with paintings, but once he finishes a painting he’s left in absolute bliss for a few days. Then he picks up his brush and demons come back and he’s back in a sense of torture’. This is not a one-size-fits-all approach to the creative process, each will find their own way, but I quite like the days I’m tortured, because the days I’m not feeling greaaaaat.

In his book ‘No Man is an Island’, Thomas Merton wrote, “Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.” How does this resonate with you?

The idea of finding ourselves and losing ourselves are the same thing. The creative process is both introspective and extrospective. We sometimes need to reflect on ourselves which requires an openness and receptiveness, and we sometimes need the willingness to leave the paddock and our own preconceptions of ourselves behind to see a new perspective. Both are vital if we are to keep the authenticity and connection to the world around, while also developing our own voice.

See more of William Grob’s work and keep up to date with upcoming exhibitions: Instagram | Website